That's it. There is nothing else.

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (Sam Peckinpah, 1973)

![]()

I wrote a piece earlier this week about 10 things I'd learned from reading Paul Seydor's recent book on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, but I fancied sharing some of my own thoughts on the movie, and what better way than by treating myself to a home viewing of the 1988 Turner Preview cut:

*A FEW SPOILERS*

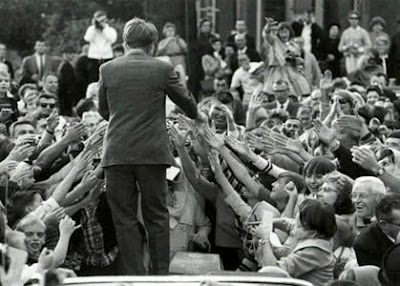

When the world’s premier director of Westerns announced that he was making a movie about Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, it seemed the perfect marriage of artist and endeavour, but everything went wrong. Studio politics, an influenza epidemic and Peckinpah’s own self-destructive behaviour turned a dream project into a nightmare, and when a truncated version of this bleak, knackered Western about the dying of a world reached cinemas, it left critics fuming and audiences cold.

Fast forward 15 years to 1988 and Turner’s unveiling of a version hurriedly prepared for the first test screening, which ran 16 minutes longer and included several unseen or extended sequences, including the ‘Tuckerman’s Hotel’ chapter featuring Elisha Cook, Jr, an epilogue that revisits the prologue, creating a full framing device, and longer versions of the first scene in Fort Sumner, the prison escape and Peckinpah’s appearance as the coffin maker. Less auspiciously, the edit was missing the scenes between Garrett and his wife, Chisum (Barry Sullivan) and prostitute Ruthie Lee (the former cut in error), and wasn’t looped, fine cut or finished, slightly undermining the idea that it was somehow a definitive version of the film. As Peckinpah scholar Paul Seydor has made clear in his fine book on the film: there is no definitive version.

In any edit, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is a compromised, sometimes confused film that manages to both debunk and pay homage to the mythos of the Old West, as newly-elected sheriff Pat Garrett slowly circles his old friend Billy the Kid who is, in the words of Townes Van Zandt, “just waiting around to die”. Garrett, as realised by James Coburn, is implacable, instinctive and methodical, effortlessly in command in any scenario, for all the good it does him. He is a man who is never at peace, and whose only evident ethos is to do a job well. Billy (Kris Kristofferson) is a round-faced, carousing kid gone slightly to seed, whose much-heralded freedom seems simply to be the freedom to bum around whoring and shooting up places, his existence essentially meaningless and inert, as he threatens revenge or revelation, but only ever acts to reinstate a status quo.

This episodic movie alternates between the protagonists, and though some of the chapters are sluggish or lacking Peckinpah’s usual punch (the prostitutes montage is absolutely shit), there are several masterpieces: Charlie Bowdre’s death scene; the murders of Bell and Ollinger with a line torn from history (the pre-emptive: “And he’s killed me too”); the taut, hard-nosed suspense sequence and gun duel at Horrell’s trading post, featuring Alamosa Bill (Jack Elam); the pastoral but ominous, eerie raft scene (which plays perfectly without words, a late decision by Peckinpah); and the climactic passage, which floors and astounds me, no matter how many times I see it. Though the death of Slim Pickens’ Sheriff Brady by the river is my favourite scene in the picture, it plays so much better in the 2005 Special Edition, which simply added several missing scenes to the extant theatrical edit (as well as re-cutting the prologue), and so features Dylan’s ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’ vocal here, as well as possessing a vibrancy in the colours that has been lost in the degrading stock of the Preview edit (only one copy of which ever existed).

Those passages of sustained brilliance, and the film’s general audacity of vision – entirely shorn of glamour and romance – are allied to a presentation of the West that I find both horrifying and seductive. Leonard Maltin complained in his review of the film that “there isn’t enough contrast in the two low-key performances”, but it’s that complexity of characterisation I find so fascinating. Peckinpah and screenwriter Wurlitzer show legality and wrongdoing as simply a matter of timing, deftly and superbly articulating the ease with which outlaws and lawmen swapped places.

Peckinpah never finished the film and never made another Western, but what he left here (quite literally, actually, quitting the film after the second preview) is a remarkable if uneven achievement. He only told Seydor that he regretted the film sinking from trace because it was “one of Jimmy Coburn’s best performances” and I’d go further – it’s simply his best. Nothing else he did approached the multi-faceted, morally labyrinthine Garrett, the character’s inner life laid bare across 122 minutes, and though Kristofferson can’t match him and Dylan can’t act (or at least can’t speak dialogue, his Chaplinesque presence is genuinely effective), the supporting cast is one for the ages, with fine work from Sullivan, Elam, Pickens, Cook, Chill Wills, Katy Jurado, Paul Fix, Harry Dean Stanton and Gene Evans. The film can be shabby and shambling and silly, frustratingly imperfect and banteringly macho in the most tiresome way, but it’s also one of the most original, important and poetic Westerns ever made: the slow, circuitous slaughter of a man resigned to his fate by another trying to change his destiny and his duty. (4)

***

![]()

CINEMA: Casque d'Or (Jacques Becker, 1952)– Man, I love French films: their easy sensuality and heavy irony, their crushing cynicism and sparkling wit, and the apparently effortless technical fluidity that so often leaves their British counterparts trailing in the dirt. This one is from Jacques Becker, whose other best-known movie was the film noir Touchez pas au grisbi, and for a long time it's wonderful: a crime-flavoured turn-of-the-century rom-com based on a notorious tabloid scandal, and full of sex and danger and moustaches.

Simone Signoret is absolutely enchanting as Marie, a prostitute in the Paris of 1902 (her blonde hair the 'golden helmet' of the title), who ditches brutish pimp Raymond for carpenter Manda (Serge Reggiani), a man who really loves her. Their halting romance leads to tragedy, thanks in part to the machinations of local crime kingpin Leca (Claude Dauphin), a sadistic, manoeuvring misogynist so utterly vile he should be in Trump's cabinet.

It's a film full of surprises, of irony and of heady moods, each one effortlessly evoked by Becker's thoughtful direction and Signoret's intoxicating performance: she falls in love with us on a dancefloor (her eyes somehow trained unstintingly on us, and on Manda, even as she turns), surprises us in a blissful bucolic neverworld, and watches from the window of a cheap hotel as fatalism plunges her into the unthinkable.

It's such a superb performance, perhaps the best of hers that I've seen: playful, amusing and appealing, her Marie so ridiculously sexy and thoroughly decent, yet also largely credible as a powerless whore in a brutal, unforgiving man's world that may be stylistically sanitised for '50s cinema, but is just as emotionally uncompromising as it should be, Becker steadfastly refusing to sugarcoat or dress up the compromises she's forced to make, most strikingly in one particularly sickening moment in Dauphin's apartment. That it follows hot on the heels of that utterly beautiful sequence in the church (my favourite scene of the film) makes it even harder to take.

It's the story that lets Signoret down, the plotting starting to plod after a lo-fi prison escape attempt, as if someone nudged Becker and handed him a checklist of film noir clichés and weepie tropes, compounding the compromises of a slightly synthetic period atmosphere (despite a compressed, repressed intensity about Reggiani, in this distracting get-up it's hard to be immersed in his plight). There are still a couple of fine, wry touches in the closing reels, but the final third lacks the distinctiveness and novelty of what precedes it, and gives its star less to do − or at least less interesting things to do.

Tragedies, least of all conventional ones that force her to suffer, were never really Signoret's forte: she was too lively and saucy and tough-but-tender. When I say I love French films, that encompasses so many of hers, but I'll always love the acidic tang of Les Diaboliques, La Ronde's effortless panache, the weighty dynamism of Melville's Army of Shadows and this one's irresistible first hour more than, say, the formulaic functionality of Thérèse Raquin or Casque d'Or's over-familiar closing reels. (3)

***

![]()

CINEMA: Fat City (John Huston, 1972)– An unglamorous, unsentimental and uncompromising boxing flick, with John Huston trying on some New Hollywood togs and finding that they suit him just fine. For an hour, he bobs and weaves – playing much of the story for laughs – before whacking us repeatedly in the solar plexus, as his film finds both its rhythm and its raison d'être.

Stacy Keach is down-and-out ex-boxer, Billy Tully, his zigzag descent into manual labour, irreleverance and alcoholism contrasted with the similarly haphazard ascent of pretty-boy pugilist, Ernie Munger (Jeff Bridges). We never see Bridges win a fight, and we never see Keach lose one, but by the end of the film, one has the American Dream and the other is fagged out and fucked.

I'm not an enormous fan of that first hour: it commences with back-to-back scenes soundtracked only by songs – while both sequences are fine in themselves, that quirk is without real artistic or dramatic value – and when the film does get going, its moments of everyday tragedy are somewhat lost in an episodic structure and a style that leans too much towards the glib and cartoonish.

It's not unusual for Huston to segue from comedy to pain (as I believe Tom Jones once sang): he did it in his two great late films, Wise Blood and The Dead, but there it was underscored by melancholia, rather than interrupting it. It doesn't help that several of the bit players can't really act.

In the final 40, though, the gloves come off, and the film's punches begin to really land. The virtues that have been obscured by padding and side-stepping become blindingly obvious: Keach's bruising, multi-layered performance, the bitter poetry of Leonard Gardner's dialogue, Susan Tyrell's fantastically annoying turn as the tragic, throaty, and self-pitying Ona, and Conrad L. Hall's sumptuous cinematography, which captures both the glory of a Californian summer and the horror of perhaps cinema's worst home-cooked meal.

These final reels hinge on a thrilling, gruelling and magnificently ugly fight, and the unceremonial slide to the bottom that follows it, closing with one of my favourite unresolved endings (or is it? From this one scene, perhaps we can plot these characters' next 10 years). But what heralds them is a scene every bit as remarkable, as Keach's manager turns up to drag him out of a bar, and the grey-faced, drink-sodden fighter lets it all hang out. "Ever since my wife left me, it's just been one thing after another," he says, and it's so raw I had to catch my breath. (3)

***

Thanks for reading.

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (Sam Peckinpah, 1973)

I wrote a piece earlier this week about 10 things I'd learned from reading Paul Seydor's recent book on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, but I fancied sharing some of my own thoughts on the movie, and what better way than by treating myself to a home viewing of the 1988 Turner Preview cut:

*A FEW SPOILERS*

When the world’s premier director of Westerns announced that he was making a movie about Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, it seemed the perfect marriage of artist and endeavour, but everything went wrong. Studio politics, an influenza epidemic and Peckinpah’s own self-destructive behaviour turned a dream project into a nightmare, and when a truncated version of this bleak, knackered Western about the dying of a world reached cinemas, it left critics fuming and audiences cold.

Fast forward 15 years to 1988 and Turner’s unveiling of a version hurriedly prepared for the first test screening, which ran 16 minutes longer and included several unseen or extended sequences, including the ‘Tuckerman’s Hotel’ chapter featuring Elisha Cook, Jr, an epilogue that revisits the prologue, creating a full framing device, and longer versions of the first scene in Fort Sumner, the prison escape and Peckinpah’s appearance as the coffin maker. Less auspiciously, the edit was missing the scenes between Garrett and his wife, Chisum (Barry Sullivan) and prostitute Ruthie Lee (the former cut in error), and wasn’t looped, fine cut or finished, slightly undermining the idea that it was somehow a definitive version of the film. As Peckinpah scholar Paul Seydor has made clear in his fine book on the film: there is no definitive version.

In any edit, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is a compromised, sometimes confused film that manages to both debunk and pay homage to the mythos of the Old West, as newly-elected sheriff Pat Garrett slowly circles his old friend Billy the Kid who is, in the words of Townes Van Zandt, “just waiting around to die”. Garrett, as realised by James Coburn, is implacable, instinctive and methodical, effortlessly in command in any scenario, for all the good it does him. He is a man who is never at peace, and whose only evident ethos is to do a job well. Billy (Kris Kristofferson) is a round-faced, carousing kid gone slightly to seed, whose much-heralded freedom seems simply to be the freedom to bum around whoring and shooting up places, his existence essentially meaningless and inert, as he threatens revenge or revelation, but only ever acts to reinstate a status quo.

This episodic movie alternates between the protagonists, and though some of the chapters are sluggish or lacking Peckinpah’s usual punch (the prostitutes montage is absolutely shit), there are several masterpieces: Charlie Bowdre’s death scene; the murders of Bell and Ollinger with a line torn from history (the pre-emptive: “And he’s killed me too”); the taut, hard-nosed suspense sequence and gun duel at Horrell’s trading post, featuring Alamosa Bill (Jack Elam); the pastoral but ominous, eerie raft scene (which plays perfectly without words, a late decision by Peckinpah); and the climactic passage, which floors and astounds me, no matter how many times I see it. Though the death of Slim Pickens’ Sheriff Brady by the river is my favourite scene in the picture, it plays so much better in the 2005 Special Edition, which simply added several missing scenes to the extant theatrical edit (as well as re-cutting the prologue), and so features Dylan’s ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’ vocal here, as well as possessing a vibrancy in the colours that has been lost in the degrading stock of the Preview edit (only one copy of which ever existed).

Those passages of sustained brilliance, and the film’s general audacity of vision – entirely shorn of glamour and romance – are allied to a presentation of the West that I find both horrifying and seductive. Leonard Maltin complained in his review of the film that “there isn’t enough contrast in the two low-key performances”, but it’s that complexity of characterisation I find so fascinating. Peckinpah and screenwriter Wurlitzer show legality and wrongdoing as simply a matter of timing, deftly and superbly articulating the ease with which outlaws and lawmen swapped places.

Peckinpah never finished the film and never made another Western, but what he left here (quite literally, actually, quitting the film after the second preview) is a remarkable if uneven achievement. He only told Seydor that he regretted the film sinking from trace because it was “one of Jimmy Coburn’s best performances” and I’d go further – it’s simply his best. Nothing else he did approached the multi-faceted, morally labyrinthine Garrett, the character’s inner life laid bare across 122 minutes, and though Kristofferson can’t match him and Dylan can’t act (or at least can’t speak dialogue, his Chaplinesque presence is genuinely effective), the supporting cast is one for the ages, with fine work from Sullivan, Elam, Pickens, Cook, Chill Wills, Katy Jurado, Paul Fix, Harry Dean Stanton and Gene Evans. The film can be shabby and shambling and silly, frustratingly imperfect and banteringly macho in the most tiresome way, but it’s also one of the most original, important and poetic Westerns ever made: the slow, circuitous slaughter of a man resigned to his fate by another trying to change his destiny and his duty. (4)

***

CINEMA: Casque d'Or (Jacques Becker, 1952)– Man, I love French films: their easy sensuality and heavy irony, their crushing cynicism and sparkling wit, and the apparently effortless technical fluidity that so often leaves their British counterparts trailing in the dirt. This one is from Jacques Becker, whose other best-known movie was the film noir Touchez pas au grisbi, and for a long time it's wonderful: a crime-flavoured turn-of-the-century rom-com based on a notorious tabloid scandal, and full of sex and danger and moustaches.

Simone Signoret is absolutely enchanting as Marie, a prostitute in the Paris of 1902 (her blonde hair the 'golden helmet' of the title), who ditches brutish pimp Raymond for carpenter Manda (Serge Reggiani), a man who really loves her. Their halting romance leads to tragedy, thanks in part to the machinations of local crime kingpin Leca (Claude Dauphin), a sadistic, manoeuvring misogynist so utterly vile he should be in Trump's cabinet.

It's a film full of surprises, of irony and of heady moods, each one effortlessly evoked by Becker's thoughtful direction and Signoret's intoxicating performance: she falls in love with us on a dancefloor (her eyes somehow trained unstintingly on us, and on Manda, even as she turns), surprises us in a blissful bucolic neverworld, and watches from the window of a cheap hotel as fatalism plunges her into the unthinkable.

It's such a superb performance, perhaps the best of hers that I've seen: playful, amusing and appealing, her Marie so ridiculously sexy and thoroughly decent, yet also largely credible as a powerless whore in a brutal, unforgiving man's world that may be stylistically sanitised for '50s cinema, but is just as emotionally uncompromising as it should be, Becker steadfastly refusing to sugarcoat or dress up the compromises she's forced to make, most strikingly in one particularly sickening moment in Dauphin's apartment. That it follows hot on the heels of that utterly beautiful sequence in the church (my favourite scene of the film) makes it even harder to take.

It's the story that lets Signoret down, the plotting starting to plod after a lo-fi prison escape attempt, as if someone nudged Becker and handed him a checklist of film noir clichés and weepie tropes, compounding the compromises of a slightly synthetic period atmosphere (despite a compressed, repressed intensity about Reggiani, in this distracting get-up it's hard to be immersed in his plight). There are still a couple of fine, wry touches in the closing reels, but the final third lacks the distinctiveness and novelty of what precedes it, and gives its star less to do − or at least less interesting things to do.

Tragedies, least of all conventional ones that force her to suffer, were never really Signoret's forte: she was too lively and saucy and tough-but-tender. When I say I love French films, that encompasses so many of hers, but I'll always love the acidic tang of Les Diaboliques, La Ronde's effortless panache, the weighty dynamism of Melville's Army of Shadows and this one's irresistible first hour more than, say, the formulaic functionality of Thérèse Raquin or Casque d'Or's over-familiar closing reels. (3)

***

CINEMA: Fat City (John Huston, 1972)– An unglamorous, unsentimental and uncompromising boxing flick, with John Huston trying on some New Hollywood togs and finding that they suit him just fine. For an hour, he bobs and weaves – playing much of the story for laughs – before whacking us repeatedly in the solar plexus, as his film finds both its rhythm and its raison d'être.

Stacy Keach is down-and-out ex-boxer, Billy Tully, his zigzag descent into manual labour, irreleverance and alcoholism contrasted with the similarly haphazard ascent of pretty-boy pugilist, Ernie Munger (Jeff Bridges). We never see Bridges win a fight, and we never see Keach lose one, but by the end of the film, one has the American Dream and the other is fagged out and fucked.

I'm not an enormous fan of that first hour: it commences with back-to-back scenes soundtracked only by songs – while both sequences are fine in themselves, that quirk is without real artistic or dramatic value – and when the film does get going, its moments of everyday tragedy are somewhat lost in an episodic structure and a style that leans too much towards the glib and cartoonish.

It's not unusual for Huston to segue from comedy to pain (as I believe Tom Jones once sang): he did it in his two great late films, Wise Blood and The Dead, but there it was underscored by melancholia, rather than interrupting it. It doesn't help that several of the bit players can't really act.

In the final 40, though, the gloves come off, and the film's punches begin to really land. The virtues that have been obscured by padding and side-stepping become blindingly obvious: Keach's bruising, multi-layered performance, the bitter poetry of Leonard Gardner's dialogue, Susan Tyrell's fantastically annoying turn as the tragic, throaty, and self-pitying Ona, and Conrad L. Hall's sumptuous cinematography, which captures both the glory of a Californian summer and the horror of perhaps cinema's worst home-cooked meal.

These final reels hinge on a thrilling, gruelling and magnificently ugly fight, and the unceremonial slide to the bottom that follows it, closing with one of my favourite unresolved endings (or is it? From this one scene, perhaps we can plot these characters' next 10 years). But what heralds them is a scene every bit as remarkable, as Keach's manager turns up to drag him out of a bar, and the grey-faced, drink-sodden fighter lets it all hang out. "Ever since my wife left me, it's just been one thing after another," he says, and it's so raw I had to catch my breath. (3)

***

Thanks for reading.